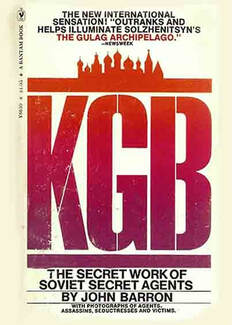

[‘KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents’ is a famous book written by John Barron. It was first published by the Reader’s Digest in January 1974. Bantam edition was published in December 1974. This book entails the history and real world espionage works of Soviet secret service – KGB. How this once dreaded intelligence agency worked during cold war era is a testimony of time. In our current issue we present a portion from this book.]

Copies of an urgent cable from the KGB Resident in New York, Boris lvanov, were rushed to Politburo members early on the morning of October 30, 1963. Ivanov reported that during the night the FBI had captured three KGB officers in the company of an American engineer, John W. Butenko…

Two officers who enjoyed diplomatic immunity because of assignments to the United Nations were released. But the third, Igor Aleksandrovich Ivanov, whose cover as an Amtorg trading corporation chauffeur provided no immunity, had been jailed along with Butenko. The cable emphasized that the FBI had confiscated enough evidence in the form of stolen secret documents and electronic and photographic equipment, to imprison Igor for a long time.

At mid-morning General Oleg Mikhailovich Gribanov, head of the Second Chief Directorate of the KGB, summoned Yuri Ivanovich Nosenko, deputy director of the department responsible for operation against American tourists in the Soviet Union. He explained the crisis and announced that the KGB had resolved to capture an American hostage to force an exchange for Ivanov. “What tourists have you got?” he asked.

“It’s the end of the season,” Nosenko replied with a shrug.

“There must be somebody,” Gribanov insisted. “Well, there is Professor Barghoorn.”

“Who is he?” Gribanov asked eagerly.

Typically, the KGB knew all about the American visitor, and Nosenko recounted his past in detail, A political scientist at Yale University, Frederick C. Barghoorn had served at the U.S. embassy in Moscow during World War II and subsequently with the State Department in Germany. The KGB believed that while in Germany he had talked with Soviet defectors and that some of his postwar visits to the Soviet Union wre financed by American foundations.

Gribanov beamed, “It’s clear. He’s a spy.”

Nosenko replied that his department had scrutinized Barghoorn’s every action during each of his visits and satisfied itself that he was not a spy. He pointed out that just a few days before, in Tbilisi (Tiflis), the KGB had drugged Barghoorn’s coffee and made him so violently ill that he required hospitalization. Its purpose in incapacitating him was to search his clothes and notes, yet nothing incriminating was found, “He is interested in our country; that’s his field. He has written three books about the Soviet Union,” Nosenko said. “But he is no spy.”

“Then make him a spy!” Gribanov commanded. That afternoon the KGB Disinformation Department gave Nosenko false documents ostensibly containing data about Soviet air defenses, and he drafted an operational plan. Because Khrushchev was away from Moscow, KGB Chairman Vladimir Yefimovich Semichastny on the morning of October 31 telephoned Leonid Brezhnev, who agreed with the “principle of reciprocity” and casually approved the KGB plan on behalf of the Politburo. “We have the go,” Gribanov told Nosenko shortly afterward.

The evening of October 31 was Barghoorn’s last in Moscow, and he stopped at the apartment of American charge d’affaires Walter Stoessel for a farewell drink. Stoessel sent the professor back to the Metropole Hotel in Ambassador Foy D. Kohler’s official car. As Barghoorn stepped toward the hotel entrance, a young Russian hurried over and tried to hand him some documents. As soon as Barghoorn touched them, KGB agents seized him from behind and carted him off to a militia station. He was then transferred to Lubyanka Prison, where he was locked up alone in a cell with a copy of Theodore Dreiser’a An American Tragedy.

Ambassador Kohler’s Soviet chauffeur, a KGB agent, did not advise the U.S. embassy of what had happened, and the Americans in Moscow assumed that Barghoorn had departed on November 1 as planned. They did not learn of his arrest on espionage charges until the KGB began to transmit the signal: Barghoorn for lvanov.

President Kennedy asked each division af American intelligence whether Barghoorn was in fact involved in any kind of espionage mission. Assured that Barghoorn was not, Kennedy at a press conference on November 14 denounced the Soviet action and demanded Barghoorn’s immediate release. Stunned by the indignant personal intervention of the President, the Kremlin was mortified. Amid alarms and consternation, Khrushchev flew back to Moscow. In his eyes, the crime was not the abduction and framing of an American professor; it was that the American appeared to be a friend of Kennedy’s. Which idiot, he demanded to know, authorized this mad venture? Meekly, Semichastny and Gribanov pointed to Brezhnev, who exclaimed: “Oh, no! They didn’t tell me he was a friend of Kennedy’s. I did not approve such a thing.”

On November 16 Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei A. Gromyko, acting upon Khrushchev’s orders, informed the United States that despite all Professor Barghoorn had done, he was being released.

That the leaders of a great nation should take time from affairs of state to concern themselves with squalid details of kidnapping and blackmail may seem incongruous. Nonetheless, the intimate, personal involvement if Soviet rulers in the operations of the KGB is commonplace. Moreover, it is the natural outgrowth of a spirit that has suffused the Soviet leadership from Lenin to Brezhnev-the spirit of the Cheka.

Since the days of the Cheka, the secret political police has been reorganized and retitled many times, becoming successively the GPU, the OGPU, the GUGB/NKVD, the NKGB, the MGB, and the KGB. But their mentality, ideals, and aims have always been the same. So has their relationship to Soviet rulers, the party, and the people. The origins and evolution of this relationship beginning with the Cheka demonstrate why it will be exceedingly difficult for any Soviet leaders to lessen their dependency upon the KGB.

Established as an investigative agency on December 20, 1917, the Cheka swiftly transformed itself into a vengeful political police force committed to extermination of ideological opponents. Ferocious statements by its founding director, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, in 1918 proclaimed its temper: “We stand for organized terror … The Cheka is not a court … The Cheka is obliged to defend the Revolution and conquer the enemy even if its sword does by chance sometimes fall upon the heads of the innocent.”

During the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath, Chekists shot, drowned, bayoneted, and beat to death an estimated 200,000 people in “official” executions, those more or less authorized. Probably another 300,000 or more died in the executions following suppression of many local uprisings or as a result of conditions in Chekist concentration camps. All these barbarities were perpetrated in accord with sweeping Party mandates that sanctioned terror, indeed demanded it. No one incited the Cheka more enthusiastically than Lenin. When idealistic communists protested Cheka sadism, Lenin in June 1918 retorted: “This is unheard of! The energy and mass nature of terror must be encouraged.” He ridiculed the communists who objected to Cheka terror as “narrow-minded intelligentsia” who “sob and fuss” over little mistakes. And he sent telegrams to Cheka officials in Penza commanding them to employ “merciless mass terror.”

In theory, the Cheka and its terror no longer were necessary once the communists overcame the last armed resistance to the Revolution. A fundamental tenet of Marxism, espoused by Lenin, asserted that workers and peasants, upon being liberated by revolution, would rally to form a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Inspired by this precept, workers in industrial Europe would rise up in contagion to create world revolution, and the resultant society would be governed not by coercion but the “direct rule of the masses.”

But at the end of the civil war, reality differed from Marxist theory. Violent opposition to the communists erupted among workers and peasants in the form of strikes, demonstrations, and riots. The most shocking trouble occurred in March 1921 at the Kronstadt naval base near Petrograd. Red sailors, who ever since 1917 had been in the vanguard of the Revolution, issued a manifesto accusing the communists of having “brought the workers, instead of freedom, an ever-present fear of being dragged into the torture chambers of the Cheka, which exceeds by many times in its horrors the gendarmerie administration of the Czarist regime.” Now the communists were forced to loose the Cheka on the very people in whose name the Revolution had been undertaken. Lenin despaired. “We have failed to convince the broad masses.” The consequences were profound.

Lenin perceived that as a minority representing virtually no one but themselves, the communists could survive and rule only through force. He reiterated that their dictatorship must be based “directly on force,” Proposing a new criminal code in 1922, he wrote Justice Commissar Dmitri Ivanovich Kursky: “The courts must not ban terror…. But must formulate the motives underlying it, legalize it as a principle, plainly without make-believe or embellishment. It is necessary to formulate it as widely as possible.”

While terrorizing the general population, Lenin also turned on the socialist factions that had fought alongside the communists, arrested their leaders, and in 1922, staged the first of the Moscow show trials. Then he proceeded to eradicate democracy within the Communist Party itself.

As Lenin destroyed the right of members to debate, disagree, and advocate their own ideas, the Party became an exclusive order through which the privileged could gain preferred status and perquisites in exchange for unquestioning obedience. Member formed what Milovan Djilas terms the New Class and acquired an overriding selfish interest in sustaining the Party that favored them with income, status, housing, food, merchandise, and leisure denied the general population. But the whole power of the Party resided with whichever oligarchs succeeded in capturing control of the leadership. As Robert Conquest states in his epic The Great Terror: “The answer to the question ‘Who will rule Russia?’ Became simply, ‘Who will win a faction fight confined to a narrow section of the leadership?”

By 1924, when Lenin lay disabled and dying from strokes, he had already cast the mold of future Soviet society. He had bequeathed the Russian people dictatorship by an oligarchy, supported by a privileged New Class, wholly dependent upon a political secret police force. He had securely established the principle, practice, and mechanism of political police force and terror as the foundation of the dictatorship. Concentration camps, arrest on the basis of class, sentences and executions without trial, the extorted confession for purposes of a show trial, the hidden informant, the concept of “merciless mass terror” were introduced not by Stalin but by Lenin. The terror decried decades later as Stalinism was pure Leninism, practiced on a grandiose and inane scale.

To Be Continued…